possible odyssey topic

Make sure you read all the way through to the end of this article. You will be asked to state whether or not you believe your actions are not caused by you at some point in the next class.

The frustrating thing about this unit is the fact that many people out there outside of philosophy (and some inside, who should know better) have taken the word "determinism" and added things to it. Specifically, some people have added to determinism the idea that free will doesn't exist. This is a truly bizarre thing to do, and it is not the way the word is used in science and philosophy, but many, many people do this. (It's very much like racial prejudice, sexism and homophobia, in which people assume all kinds of horrible things about other people merely because the other person is a different race, or female, or homosexual, or . . .) So I want to get one thing straight from the very beginning, the term "determinism" does not include the idea that free will is absent. If I say that an action was determined I am absolutely NOT saying that it was not free-willed.

There is no assigned reading Does the Center Hold? for this unit. Donald Palmer's discussion of this issue is so bad that reading it can only hurt your understanding of this issue. For this reason, I would very much prefer that you do not read our text about this issue. (This prohibition does not apply to anyone who choose to write about Palmer's views on free will and determinism for their essay topic, as they might need to re-read Palmer to complete that assignment.)

This chapter is intended to cover the following topics.

1. The definition of determinism (aka

"necessity" and "nonrandomness"), and how it is

different from things like coercion, programming, predetermination,

predestination and nofreewillism.

2. The definition of

indeterminism (a.k.a. "randomness"), how it is different

from controlability and predictability, and what this means for the

role of determinism in our experience.

3. The relationship

between determinism and predictability, how it is that predictability

implies determinism but determinism does not imply

predictability.

5. The difference between determinism and

programming.

6. The difference between determinism and

predetermination.

7. The difference between determinism and

predestination.

8. The difference between determinism and

indeterminism.

9. The difference between nofreewillism and

determinism.

10. The definitions of "volitional

determinism" and "volitional indeterminism."

3.

The doctrine of Laplace, and what it means for determinism and

predictability in the world.

4. The doctrine of D'Holbach, and

what it means for for determinism and predictability in human

beings.

To

prepare, I want you to be able to do the following.

1.

Understand the definitions of "necessity," "randomness"

and "freedom."

2. Understand the logical implications

of saying that an event did not

happen out of necessity.

3. Understand the logical implications of

saying that an event did not happen randomly.

At

this point I want to remind you, in the strongest possible terms,

that the textbook isn't necessarily right about everything. In my

view, the textbook is quite clearly wrong about several

vitally important points. This is part of the reason you only have a

few pages of reading for the next few classes. It's hard to read a

textbook critically, but you've got to be able to do it if you're

going to be able to do any kind of real intellectual work.

The

other thing I want you to think about here is that the issues we will

cover here will require us to think very carefully and logically

about the precise nature of various concepts, and what the features

of those concepts imply about the relationships between them. For

this reason, it is of paramount importance that we all understand

precisely what the correct definitions of these concepts are. So make

sure you read carefully, and do your best to understand the

definitions and examples for this section of the course.

Again,

as you read this, it's important to remember that the definition of

"determinism" does not include any reference to free will.

It most especially does not include any suggestion that free will

does not exist. got that? Determinism does not

say that free will doesn't exist.

Determinism

Determinism

is also known as "necessity" and "nonrandomness."

Whenever you see the word "necessity," remember that it

means exactly the same as "determinism." Whenever you see

the word "nonrandomness," remember that it means exactly

the same as "determinism."

It should go without

saying that the word "necessity" does not suggest that free

will doesn't exist, and that the word "nonrandomness" also

does not suggest that free will doesn't exist.

Determinism

is the doctrine that events are not

random. This means that every

event that ever happens in a deterministic system is precisely caused

by the ensemble of relevant conditions that immediately

preceded it. A slightly different ensemble of conditions may or may

not produce a significantly different event, but exactly

the same conditions will always

produce exactly

the same event. This potentially applies to every object and

condition in the universe, even humans. If you are a deterministic

system, and if we could recreate exactly the same conditions that

existed at eleven o'clock yesterday morning you would do exactly the

same thing that you did do at eleven o'clock yesterday morning. If we

were to recreate exactly

the same conditions that existed just before the last time you

ordered chocolate ice cream, you would order chocolate ice cream. (Of

course, you wouldn't know you were orderining it again,

because your memories would be exactly the same as they were just

before the first time.)

Indeterminism

(or "randomness") is the denial of determinism. It is

therefore the doctrine that events are

random. Events that happen in indeterministic systems are not

precisely caused by the ensemble of relevant conditions that

immediately preceded them. In a system that is not deterministic, the

exact same ensemble of conditions will not

necessarily produce the same result. (In fact, a group of objects

that are indeterministicly related to each other cannot really be

called a "sysyem", because the concept of a system

depends the objects being able to affect each other, and that

requires at least some degree of determinism.) This also potentially

applies to every object and condition in the universe, even humans.

If you are not

a deterministic system, then being in the condition of being

absolutely determinined to do something has absolutely nothing to do

whith whether or not you go it. Even if you experience yourself as

choosing to order ice cream, that isn't necessarily what you will do.

In fact, if your brain isn't deterministic, there is virtually no

chance that you will actually do any of the things you choose to

do.

Volitional

determinism is the doctrine

that people's volitions all follow by necessity from their

immediately preceeding brain states. The state of your brain at time

t-0 precisely determines the decision you make at time

t-1.

Volitional

indeterminism is the doctrine that people's volitions

are all random with respect to their immediately preceeding brain

states. The decision you make at time t-1 has nothing to do with

state of your brain at time t-0.

In

terms of indeterminism, the phrase "you could do anything"

does not mean you

could choose

to do anything you choose

to do. It means you could find

yourself doing anything at all, no

matter what you

choose to do. Say you choose to respond to a red "don't walk"

sign by stopping at the curb by a crosswalk. (Maybe you do this

because you don't want to get run over - which would be an example of

determinism.) But let us also say that at the moment you chose to

stop, indeterminism kicks in, and "you could do anything"

in the indeterministic sense

of "could do anything." You want to keep standing on the

curb, but you could find yourself attempting a back flip. (Remember,

this is indeterminism. What you want does not determine what you do.)

Or you could dance out into traffic. I don't mean that you could

choose

to dance into traffic. Indeterminism means that what you choose to

does not determine what you do. What indeterminism means that you

could dance out into traffic even you desperately want not

to. In fact, it means that you

could dance into traffic even if you choose

not to. That's right, you choose

to do one thing, and despite that, you do something completely

different, and perhaps suicidal.

General

Determinism (usually just "determinism") is the

doctrine that everything in the universe, not just our

volitions, but everything, is determined. If general determinism is

true, volitional determinism will certainly be true and quantum

indeterminiacy will be false. If quantum indeterminacy is true,

general determinism will be false. However, if general determinism is

indeed false, volitional determinism can easily still

be true. This is because volitional

determinism is logically

compatible with quantum

indeterminacy. Quantum indeterminacy, which may or may not be

true, is the doctrine that at least some behaviors of at least some

subatomic particles are indeterminate to the extent that the state of

a particle at time t-1 is at least sometimes not completely

determined by it's state at t-0. However, this indeterminacy is

strictly bounded, and seems limited to very small particles and in

fact supports determinism at the level of atoms and

molecules. Thus it is perfectly possible for your brain to

behave completely deterministically while at the same time billions

of subatomic particles in your brain are behaving with a

significant amount of indeterminism. (Isn't physics fun!)

Misunderstandings of

Determinism

One

of the biggest problems with discussing determinism is that many

people confuse it with programming, predetermination, predestination

and other forms of external control. This is a very dangerous

confusion, because it confuses determinism (which does not

necessarily have anything to do with free will) with situations in

which a person's actions or destiny are controlled by external forces

(which situations are usually assumed to eliminate free will, or

render it futile.) Let me be perfectly clear here. In this class,

"determinism" only refers to determinism.

It does not refer to programming, predetermination,

predestination, fate, karma or any other kind of force external to

the person that eliminates or negates her free will. It should also

be unnecessary to add that "determinism" absolutely does

not refer to "nofreewillism" or "coercion."

Coercion

is a condition such that some person is being forced to do something

against his will. It has nothing to do with whether or not a system

is deterministic. Coercion is also the only condition that can remove

free will from a physically capable human being. If an action was

coerced, then it was not free. If an action was free, then it was not

coerced. Coercion only

exists when there is an outside

force controlling what someone does. A condition would only remove

someone's free will if it created an outside

force that overruled

the volition-creating processes in that person's brain.

For

instance, say that Pierre's internal state has determined that he

will go to church today. Unfortunately, a group of ninja have decided

to take him to a Kurosawa film festival, so they surround Pierre,

menace him with their scary black katana, and force him to go to the

festival and watch The Seven Samuari. Now in this case, Pierre's

actions were not

determined by his own internal processes, and so they were not

free.

Freewillism

(a word I made up) is the doctrine that free will exists. It is the

doctrine that, whatever else is true, people at least sometimes act

on their own free will.

Nofreewillism

(another word I made up) is the doctrine that free will does not

exist. It is the doctrine that, whatever else is true, people at

never act on their own free will.

You

need to be able to distinguish between determinism and

coercion.

Determinism is Not

Coercion

Coercion is an external force that prevents

people from what they want to do. Volitional determinism is an

internal condition that determines what people want to do. It doesn't

prevent anyone from doing anything. What it does do is allow a

person's mental states to determine what he does. This is important

because it is coercion that prevents people from acting on

their own free will. Since the only alternative to a free-willed

action is a coerced action, people who believe that determinism

is incompatible with free will will have to show how an internal

condition of determinism can reach outside of a person to create an

external condition of coercion.

Determinism Is Not

Done By People.

When an event is determined, that

means it was caused to happen by the immediately preceeding

conditions. It does not mean that the event was determined

by somebody,

Determinism Does Not

Say That Things Are Already

Determined.

If you think determinism is the doctrine

that things are determined ahead of time, you are absolutely

wrong. Deteriminism is when events are determined by the immediately

preceding conditions. Nothing is determined until the moment it

happens. so don't ever say that "deteriminsm is

the doctrine that events are determined" without pointing out

that they are determined at the instannt they happen, and not a

moment before.

Determinism Is Not

Programming.

Some people interpret determinism as

saying that people are presently equipped with programs that will

control their future actions. It is true that some psychological

theories claim that people have habitual ways of reacting to

situations, called "scripts," that cause them to behave in

certain ways. Couples who repeatedly enact exactly the same argument

over and over again can be said to be operating on scripts. The

presence of scripts in a person's mind can be said to reduce that

person's free will because that person will tend to meet the same

situation with the same response every time, instead of re-thinking,

and possibly making a new decision with each new occurrence. If a

person's script is so powerful that he cannot change the way he

reacts to certain situations, then the script could well be seen as

having eliminated his free will.

For instance, consider the

case of a woman who has been programmed to always form relationships

with arrogant men. You can make up your own story of how she got to

be programmed. You can assume she was programmed by events in her

childhood, or perhaps that she was the victim of a mad scientist. The

one thing you cannot do is assume that she was programmed by

volitional determinism, because volitional determinism cannot, and

does not, program people. Anyway, assuming that this woman is

programmed, we will infer that she is unable to resist overtures from

arrogant men. Even if it is the case that she is well aware that all

her previous relationships with arrogant men have been painful and

psychologically harmful, even if she is absolutely determined to

never again go out with another arrogant man, the fact that she is

programmed means that she will never be able to say no if an arrogant

man asks her for a date.

Determinism contradicts the

view that people are programmed. Determinism says that the woman in

the above example does not have to be programmed to always accept

dates with arrogant men. Rather, it is a says that the next time an

arrogant man asks this woman out, the decision will be determined by

the conditions that exist in her brain at that time, which

will include all her memories of painful experiences with

arrogant man, and all her previous resolutions never to date one

again. If the woman's decision is determined, rather

than programmed, she will be able to resist the arrogant man's

overtures, and indeed, will probably do so.

The doctrine

of scripts is not the doctrine of determinism. Determinism says

nothing about whether or not people are programmed. The theory of

determinism says nothing about future behavior, and in fact says

nothing specific about human beings at all. It just says that things

do not operate randomly Although some people assume that

determinism means that people are programmed, and illegitimately and

confusingly refer to this theory as "psychological determinism,"

it is absolutely wrong to assume that the doctrine of volitional

determinism is the same as this doctrine of psychological

"determinism."

If you think that volitional

determinism implies that people are programmed, then you will have to

show how the mere fact that the volitional system does not operate

randomly creates programs that prevents people from ever changing how

they react to things. If you cannot show that nonrandomness in the

brain creates programs that act on the volitional system as a kind of

external control, then you rationally should conclude that it does

not, and that determinism does not imply that people are

programmed.

Determinism Is Not

Predestination.

Sometimes, students write things like

"determinism rules out free will because, if our fate is already

decided for us, and there is nothing we can do to alter it, then we

have no free will." There are two things wrong with this. First,

it misunderstands determinism. Second, it misunderstands free

will.

Predestination is best illustrated by the story of the

Appointment.in Samarra. A man has a servant. This servant came in one

day in a state of extreme distress. He tells his master that he was

just in the marketplace and he saw Death there too. He would not have

been scared, except that Death gave him a funny look, and that

panicked him. The servant begged his master to lend him a horse, so

he could go and stay with relatives in the distant town of Samarra.

The master agreed, but after the man had ridden away, he became very

angry and decided to give Death a piece of his mind. So the master

hurried to the marketplace and confronted Death. "Why did you

give my servant that funny look," he demanded. "I'm sorry,"

Death replied, "but I was very surprised to see him here. You

see, I have an appointment with him tonight in the distant town of

Samarra."

Predestination is the claim that our fate is

already marked out as, and that there is nothing we can do to avoid

ending up there. However, predestination does not rule out free will.

The man in the story went to Samarra of his own free will. He was not

coerced. Nobody dragged him there. He struggled to avoid his fate,

but his fate caught up with him anyway. Notice that the story does

not say that he did not have a choice in what he did. The story just

said that he did not have a choice in what eventually happened to

him.

Secondly, and more importantly, predestination is

enormously different from determinism. Determinism simply does not

say that there is any inevitable fate picked out for us in advance.

If anything, determinism contradicts predestination because it says

that events are determined by present conditions, not by arbitrarily

assigned destinies.

If you want to say that determinism

implies predestination, you are going to have to come up with how

determinism can arrange for someone's destiny to be picked out in

advance, and then you're going to have to give an argument that shows

that the mere fact that people's decisions are non-random with

respect to their present brain states inevitably creates the

arbitrarily chosen destinies necessary for predestination to be true.

Again, good luck with that.

Determinism Is Not

Predetermination.

Sometimes

I see students write things like "determinism rules out free

will because, if our actions are predetermined, then they are not

chosen by us." The problem with this is that determinism does

not say actions are predetermined.

Determinism just says that actions are determined, which

is a very different thing . If an action is predetermined, that

means that some external agency decides what you are going to do

before you have had a chance to make up your own mind about

what you are going to do. (Or that you've somehow locked yourself

into a future action you are unable to change your mind about).

Determinism does not say that your actions are predetermined because

it does not say that there is any external agency that can decide

your actions for you before you make up your mind. It just says that,

when you do make up your mind, do so in a nonrandom manner.

Volitional determinism just says that your decisions are determined

by the conditions that exist inside your brain at the time

immediately preceding your decision. No external force is involved,

and the determination is made only at that point in time where you

make the decision.

For example of predetermination, consider

the example of a man who has been predetermined to buy a doughnut

with his morning coffee tomorrow. (Again, you can make up your own

story about how he became predetermined to buy that doughnut.

Whatever story you tell, make sure you remember that whatever it is

has nothing whatsoever to do with determinism.) If the man is

predetermined to buy that doughnut, then his brain state at the time

he makes the decision will have nothing whatsoever to do with what he

does. He is going to buy that doughnut, no matter what. Even if he is

absolutely determined to lose weight, even if he has come to hate

donuts, even if he has decided absolutely not to buy that doughnut,

he will buy it. That's what "predetermined" means. And it

is also the opposite of determinism. Determinism says that his brain

state, which includes all his desires and decisions, will determine

whether or not he buys the doughnut. Volitional determinism implies

that decisions are not predetermined, because it clearly implies that

decisions are only determined at the time that they are made, and not

before.

Remember, determinism just says that our decisions are

not random with respect do what is going on in our brains at the time

we make them. If the man's desire to lose weight is stronger than his

hunger and his craving for sugar, he will decline the doughnut. If

hunger and craving are stronger, he will buy the doughnut. You may

think that a condition in which a person's decisions are not random

with respect to his present brain state is not a state of free will,

but you cannot legitimately say that the nonrandomness of this

person's decisions means they are predetermined.

Predetermination

is not determinism. Determinism not only says nothing about whether

or not people's decisions can be determined for them in advance, it

actually contradicts this idea by saying that people's decisions are

determined by their brain states of hope, fear, desire, determination

and conscious thought at the time of the decision.

If you want

to think that determinism implies that decisions are predetermined as

well as determined, you have to prove two things. First, you would

have to show how a person's decision can be both determined by the

conditions that exist at the time of the decision and by some

different set of conditions that existed at some previous time.

Second, you would have to show how determinism creates the conditions

in the human brain that allow previous conditions to determine

present decisions. Good luck with that.

Determinism

is Not

Nofreewillism

Determinism

is the doctrine that events are determined by the immediately

preceeding conditions. Nofreewillism is the doctrine that free will

doesn't exist. Not only are these doctrines different, they

don't have even one single solitary term in common.

So it should be obvious that determinism isn't nofreewillism. In

fact, saying "determinism is not nofreewillism" is like

saying "basketball is not the rejection of cheese production."

"Random" in

this context, means MORE than "Unpredictible" or "Happens

For No Apparant Reason."

In

our text, Donald Palmer uses the word "random" to mean

"undetermined" which means "happens

for no reason whatsoever." In

ordinary life, we use the word "random" to mean stuff that

we could not have predicted or which happens for no apparant reason.

Both of these are perfectly compatible with determinism, because

complex deterministic systems are usually unpredictible and contain

many unseen elements. But undetermined

events don't happen

for

reasons.

If an event is undetermined, it happened for no reason whatsoever.

Since Donald Palmer is using the word "random" to mean "not

determined," it is vitally important to remember that every time

Palmer uses the word "random" it means "not

determined, and therefore happening for no reason whatsoever."

Indeterminism Is Not

Freedom

If you think

free willed actions cannot be determined, please write me an essay

explaining how your "free" actions can still be your

actions when they are completely

random with respect to your

mental state at the time you made them. (An if you think your free

actions aren't random, then you think they're determined, because

random and nonrandom are the only choices you get.)

Determinism

is

Nonrandomness.

If you

think they're different, write a paper explaining how

they're different. And then consult the definitions above to figure

out where you went wrong.

"Necessity"

is

Determinism

Well, in

this unit it is. In real life, "necessity" means something

a little different from determinism, so I don't know why Palmer uses

the word "necessity" since we already had the word

"determinism." Still, when Palmer says "necessity,"

he means "determinism."

Indeterminism

is

Randomness

It just is.

Deal with it.

Predictability

Remember, determinisim is a condition of

non-randomness.

A system is deterministic to the extent that it's behavior at any

given instant is not

random with respect to it's state in the immediately preceeding

instant. To put it another way, determinism is a condition such that

whatever happens at a given instant is fully controlled by the exact

state of the universe in the immediately preceeding instant. It is

important to remember that this is the whole definition of

determinism. Determined just

means non-random. Random just

means undetermined.

Determinism sometimes

allows predictability, if the system is simple enough that all the

important variables can be known with sufficient precision. However,

most deterministic systems are much too complicated for this to be

possible, so vast majority of deterministic systems are highly

unpredictible. For this reason,

determinism does not

imply predictibility.

Randomness does not

allow

predictability. If a system is operating without determinism, then

it's behavior at any given instant does not

depend on it's state at any preceeding instant, so knowing it's state

at any given time will not tell us anything about it's state at any

later time. Since a system can only

be predictible to the extent it is

deterministic, predictibility

implies determinism.

For

instance, say that Pierre is a very regular churchgoer, and we know

that there is absolutely nothing unusual about this Sunday morning for

Pierre. He is not sick, his family is fine, he has not had a crisis

of faith. In fact, for Pierre, this Sunday is exactly

like last Sunday. (When I say exactly,

I mean

exactly. Don't be saying to yourself, "there could be something

different." In this case, there isn't anything

different.) Given that this Sunday is exactly like last Sunday,

determinism says that Pierre will go to church, so if it turns out

that he actually does

go to church, that is evidence that determinism is true, at least for

Pierre.

Of course, in real life, we never get the exact same

conditions over again, and we also never know enough about any

situation to make accurate predictions, so most deterministic systems

are unpredictible. Still, it is a fact that predictibility is only

ever possible with deterministic

systems, so the fact you can make accurate predictions about some

systems implies that at least those systems are deterministic.

Indeterminism Makes

Control Impossible

Imagine

that your car's steering wheel is not deterministically connected to

your car's front wheel. If the connection isn't deterministic, then a

slight turn to the left won't necessarily cause the car to make a

slight turn to the left. It might make the car turn hard left

instead. It might even make a slight right turn. You just don't know.

And whatever it does this time, it won't necessarily do the same

thing the next time you turn the wheel the same way. In fact, an

indeterministic connection is just like having the steering

disconnected and the car's wheels moving randomly as you desperately

try to regain control over your vehicle. Don't try this at home.

To see how this might work for humans, read

Escape From Hell

Mountain

Indeterminism

Makes Prediction Impossible

Say

your car's wheels move randomly. Can you predict which way they'll

move next? How would you do it?

For

instance, a car appears to come out of nowhere and crashes into yours

at an intersection. For that to be an undetermined event,

the car would have had to literally not even exist before it

hit yours. If, however, the car was previously made in a factory in

Japan, shipped to America, bought by a massage therapist, and stolen

by a drunk who then ran a red light and hit your car, then the event

was actually determined, not random, and counts as an

instance of determinism in action.

Can you think of

an actual provably random event that has ever happened to you?

If

you think that all the events that happen to you happen for reasons,

you believe in determinism.

Self

Test

If you've properly studied the above materials,

the following questions should be easy to answer.

After

studying the assigned reading in the light of the following material,

you should be able to give complete and logically precise answers to

the following questions.

1. Give a complete and precise

definition of determinism, and how it is different from coercion? How

is a situation that involves coercion different

from one that merely involves determinism?

2. Give a complete

and precise definition of determinism, and how it is different from

programming? How is a situation that involves programming different

from one that merely involves determinism?

3. Give a complete

and precise definition of determinism, and how it is different from

predestination? How is a situation involving predestination different

from one that merely involves determinism?

4. Give a complete

and precise definition of determinism, and how it is different from

predetermination? How is a situation that involves predetermination

different

from one that merely involves determinism?

5. Give complete

and precise definitions of “necessity” and “randomness,”

and explain exactly how they are related to each other. Can both be

true of the same thing at the same time? Can both be false of the

same thing at the same time? Explain precisely why or why not.

6.

Explain the logical strengths and weaknesses of LaPlace’s

conjecture that if we had a certain kind of knowledge we could do a

certain thing. What knowledge would we need? What thing could we do?

Can we actually do this thing? If not, why not? If not, does the

reason why not mean there’s anything wrong with LaPlace’s

logic? Why or why not?

7. Explain and analyze the precise

logical relationship between determinism and predictability. What is

“determinism?” What is “predictability?” If

an event is determined, does that mean it has to be predictable? If

it was predictable, does that mean it had to be determined? (You can

discuss the Tacoma Narrows Bridge if that helps.)

What Does Your Gut Actually Say?

To illustrate indeterminism, as it applies to people's acts, let me lead you through the following story. Let us consider Indesmond and Detrick, two almost identical romantic young men, with identical beloveds. The only difference between Indesmond and Detrick is that Indesmond has indeterminism, (at least for important aqctions) as described by Palmer, and Detrick does not. Indesmond is madly in love with Isabelle and Detrick is madly in love with Denise. Both Indesmond and Detrick invite their beloveds on moonlight cruises, on which they both plan to make the most romantic proposals possible. Each of them has decided to marry his beloved, has purchased a tasteful ring, has formed a plan to get his beloved to the ship's rail when the moon is high and there is no sound but the sighing of the breeze and the gentle roar of the ship rushing through the wine-dark sea. Neither of them changes his mind at any point in this process. Neither of them has any reason to doubt his plan, or to do anything other than make the romantic proposal he has planned. Each of them arrives at the crucial moment exactly as planned, and neither of them has any last minute change of heart or change of intentions whatsoever. The only difference between them is that, at this point, Detrick acts deterministically and Indesmond doesn't. Detrick kneels before his beloved fully intending to propose, does not change his mind, and therefore proposes to Denise. (Awwwww.) Similarly, Indesmond kneels before his beloved fully intending to propose, and does not change his mind but, because Indesmond has indeterminism, this state of fully intending to propose, without even the suggestion of changing his mind, will not necessarily result in him proposing to Isabelle. It's true that he could propose to her, but that would be only a coincidence, since his past state of intending to propose does not determine what he will do next. In fact, Indesmond proposing to Isabelle would be an amazingly unlikely coincidence, since there are thousands of things he could do instead. He could do a backflip, he could do a Cossack dance, he could tickle Isabella, he could push her overboard, be could do anything and, because he has indeterminism at that moment, what he does next has absolutely nothing to do with what he has decided to do. This is the essential difference between Detrick and Indesmond. Detrick could also do anything, but Detrick is bound by his own intentions. Detrick could do anything he decided to do but, because Detrick is deterministic, he won't do things he hasn't decided to do. Indesmond is not bound by his own intentions. Indesmond could do anything at all, especially things he hasn't decided to do. Indesmond is not bound by his own intentions and choices, and at important moments he is very likely to do things he never decided to do.

To make this contrast as clear as possible, let us say that Indesmond has a brother, Indeiter. Just like Indesmond, Indeiter has moments when what he does next is not determined by what he has chosen to do. But Indeiter has these moments all the time. If Indeiter's brain is in a condition of really wanting to go to a restaurant, that never determines that he will go to a restaurant. If Indeiter's brain is in a condition of being terrified of bees, that never determines that he will avoid bees. What Indeiter really needs never determines what he wants, what he wants never determines what he thinks, what he thinks never determines what he decides, and what Indeiter decides to do never determines what he does. All of Indeiter's wants, thoughts, and decisions are completely indeterminate, which is to say that they are completely random.

To see how it might be like to be a little bit like Indeiter, consider the Randy Random character in Escape From Hell Mountain

You here's the question: Do you believe that people are in general like Indeiter, who continuously acts like Indesmond did when he was about to propose to Isabelle, or do you think people are like Detrick? Do you think that when people make decisions, and do not change their minds, their states of mind do not ever cause them to do what they've decided? Or do you think that people are like Detrick, that when they decide to do things, and do not change their minds, those decisions cause them to do the things they've decided to do?

If you want a little taste of what it would be like to have indeterminism in your brain, play The Indeterminism Game

Remember, if a person is like Indeiter, all her wants, thoughts, desires, decisions and actions will all be completely random with respect to each other and to her needs, background and present situation. Nothing she feels, thinks, says or does will have anything to do with anything else she feels, thinks, says, does or anything else at all.

If you think people are like Detrick and not like Indeiter, you believe in determinism.

If you believe in indeterminism (for people) you also believe that people are like Indeiter.

The Libertarian Fallacy

You don't have to actually read our textbook for this unit. There's so much in it that's wrong that I'm not sure that reading it wouldn't do more harm than good. Still, you deserve to hear the other side in this debate, so I've included optional reading assignments in this chapter which will allow you to see what Palmer says about some of the claims I make in this chapter.

If you're pressed for time, you could concentrate of finding answers to

the following questions:

1. What are the main claims of libertarianism?

2. What are the main claims of soft determinism?

3. What are the main claims of hard determinism?

4. What is the NCFW definition of free will?

5. What is the IDFW definition of free will?

6. What is the basic argument for soft determinism?

7. What is the basic argument for compatibilism?

8. What is the "incompatibilism gap?"

9. What is wrong with defining freedom as "lack of cause?"

10. What is wrong with using moral responsibility to argue against

determinism?

11. What is the "could do otherwise" argument against soft determinism?

12. What is wrong with the "could do otherwise" argument against soft

determinism?

13. How does libertarianism contradict itself?

I call this chapter “The Libertarian Fallacy” because I believe that the doctrine Palmer calls “Libertarianism” is based on logically fallacious reasoning. Hopefully, the logical properties of Libertarianism will emerge as you study the reading. (The doctrine called “libertarianism” in this chapter has nothing to do with the ethical and political doctrines that are also called “libertarianism.”)

Libertarianism, the philosophical belief about determinism and free will, is a double doctrine. Libertarianism fundamentally holds that the following two separate propositions are true:

L1. Free will exists, and

L2. Volitional Determinism is false.

I give L2 as "volitional determinism is false" instead of just "determinism is false" because many libertarians are willing to accept that such things as steamrollers, ocean liners and computers operate deterministically while denying that the will-making part of the human brain does so. They are therefore willing to accept that their cars, their coffee machines and their alarm clocks are deterministic while not accepting the same for the essential parts of their brains.

As well as these two doctrines, libertarians also tend to believe the following:

L3. Determinism rules out free will. (Belief in this proposition is called “incompatibilism.”)

To make this clear, L3 (incompatibilism) is the belief that free willed actions can't be determined actions and determined actions cannot be free willed actions. Incompatibilism holds that if a particular action was determined by its immediately preceding conditions, that particular action could not have been free willed, and that if a particular action was free willed, that particular action could not have been determined by its immediately preceding conditions.

To illustrate incompatibilism, imagine that you get the idea to buy ice cream, go into Coldstone, wait in line, get into line, reach the counter and, at the last second, don't buy ice cream after all. Further imagine that there is a reason that you don't buy ice cream at this point, and that this reason is that, at this point, you no longer feel like having ice cream. To an incompatibilist, the fact that your action to not get ice cream was determined by you no longer feeling like ice cream means that your action to not get ice cream was not a free-willed action. To incompatiblists, any action that is caused by the immediately preceding conditions cannot be a free action.

Another way to think about L3 might be to say that libertarians conceive of free actions as uncaused actions. (Palmer seems to say this on page 219 (5th Ed), 222 (4th Ed) of our text, when he says “ . . . the idea of a free action or even a free thought, conceived as an uncaused event . . . ”) I might even go so far as to say that libertarians often seem to define free willed actions as uncaused actions. I personally emphatically reject the idea that free events must also be uncaused, random events, and so I will generally treat libertarianism as merely asserting that determinism rules out free will, and not as saying that freedom is randomness. I should also point out that libertarians often seem to base their arguments for libertarianism on incompatibilism, or on the definition of free actions as uncaused actions, or on both. I hope to prove that this does not work.

Finally, in order to hold their doctrine, Libertarians MUST believe that:

L4. Lack of determinism does not rule out free will.

Look again at L1 (free will exists) and L2 (determinism is false). If it is true that free will exists and determinism is false, it has to be true that determinism being false does not rule out free will. This means that libertarians have to believe that it is possible for an action to be both free and undetermined.

To illustrate L4, imagine again that you get the idea to buy ice cream, go into Coldstone, wait in line, get into line, reach the counter and, at the last second, don't buy ice cream after all. But this time also imagine that there is absolutely no reason that you don't want to buy ice cream at this point. Nothing in your mind, or anything at all, has changed to make you no longer want ice cream. In fact, you still want ice cream, you have decided to get ice cream, and that you have even willed yourself to order ice cream, but you don't. Instead, you throw your hat at the server for absolutely no reason. You didn't want to throw the hat. You didn't feel any impulse to throw the hat. You didn't even think about your hat at all. You just threw it. (I'm not saying that this is a plausible scenario. I'm just setting this up to illustrate a logically necessary feature of libertarianism.) In this scenario, your action of throwing your hat instead of ordering ice cream was an uncaused action. To an incompatibilist, the fact that your action of throwing your hat was not determined by you does not mean that the actions was not your free willed action. To an incompatibilist, it makes perfect sense to say “that person's action was not determined by anything inside her, and it was her free willed action.”

Soft Determinism

While Donald Palmer seems to support libertarianism, I personally support a competing doctrine with the weak-sounding name of “soft determinism.”

Soft determinism is also a double doctrine. Soft determinism fundamentally holds that the following two separate propositions are true:

SD1. Free will exists, and

SD2. Determinism is true (at least

as far as human volition is concerned.)

In order to hold their doctrine, soft determinists MUST believe that:

SD3. Determinism does not rule out free will. (Belief in this proposition is called “compatibilism.”)

To make this clear, SD3 (compatibilism) is the belief that free willed actions can be determined actions and determined actions can be free willed actions. Compatibilism holds that if a particular action was determined by its immediately preceding conditions, that particular action could still have been free willed, and that if a particular action was free willed, that particular action could still have been determined by its immediately preceding conditions. (Personally, I think that if an action was free-willed, that proves that that particular action was determined. If it wasn't determined, it couldn't have been free willed. But more on that later.)

To illustrate compatibilism, imagine that you get the idea to buy ice cream, go into Coldstone, wait in line, get into line, reach the counter and, at the last second, don't buy ice cream after all. Further imagine that there is a reason that you don't buy ice cream at this point, and that this reason is that, at this point, you no longer feel like having ice cream. To a compatibilist, the fact that your action to not get ice cream was determined by you no longer feeling like ice cream does not mean that your action to not get ice cream was not a free-willed action. To compatiblists, an action that is caused by the immediately preceding conditions can be a free action.

Another way to state SD3 is to say that soft determinists do not conceive of free actions as uncaused actions, and do not define free willed actions as uncaused actions. To a soft determinist, a free action is one that you did of your own volition rather than being forced to do it. To a soft determinist, “freedom” is defined as lack of constraint by forces beyond your control.

As well as those three doctrines, soft determinists also tend to believe the following:

SD4. Lack of determinism does rule out free will.

To illustrate SD4, imagine again that you get the idea to buy ice cream, go into Coldstone, wait in line, get into line, reach the counter and, at the last second, don't buy ice cream after all. But this time also imagine that there is absolutely no reason that you don't want to buy ice cream at this point. Nothing in your mind, or anything at all, has changed to make you no longer want ice cream. In fact, you still want ice cream, you have decided to get ice cream, and that you have even willed yourself to order ice cream, but you don't. Instead, you throw your hat at the server for absolutely no reason. You didn't want to throw the hat. You didn't feel any impulse to throw the hat. You didn't even think about your hat at all. You just threw it. (I'm not saying that this is a plausible scenario. I'm just setting this up to illustrate a point about soft determinism.) In this scenario, your action of throwing your hat instead of ordering ice cream was an uncaused action. To a soft determinist, the fact that your action of throwing your hat was not determined by you means that the actions was not your free willed action. To a soft determinist, it makes absolutely no sense to say “that person's action was not determined by anything inside her, and it was her free willed action.”

To summarize:

Libertarianism

L1. Free will exists

L2. Determinism is false

L3. Determinism rules out free will. (Incompatibilism)

L4. Lack of determinism does not rule

out free will.

Soft Determinism

SD1. Free will exists

SD2. Determinism is true

SD3. Determinism does not rule out free will. (Compatibilism.)

SD4. Lack of determinism does rule

out free will.

There's one more important doctrine we can define here.

Hard Determinism

HD1. Free will does not exist.

HD2. Determinism is true

HD3. Determinism rules out free will. (Incompatibilism)

Hard determinists generally believe both HD2 and HD3, and accept HD1 as a logical consequence of combining those two beliefs.

Both libertarians and soft determinists believe in free will, although

they may define it differently.

Both libertarians and hard determinists believe in incompatibilism.

Only soft determinists believe in compatibilism.

Soft determinists define “free will” as a condition in which a person determines her own actions. If a person is prevented from doing what she wants to do, and is instead made to do something she did not personally decide to do, then that action wasn't free-willed, according to soft determinism. (I call this “Non-Coercion Free Will, ” or “NCFW”.) This is the definition of “free will” I use in this reading. When I write “free will, ” I will mean NCFW.

The Plan

My plan for the rest of this unit is as follows: First, I shall give the basic arguments for soft determinism and compatibilism (which I think are the correct theories). Second, I shall discuss what I take to be the most strongest objections to soft determinism (starting with the easiest) and, in each case, tell you why I think that the objection fails to refute soft determinism. (Additional objections will be available in optional reading.) Third, I shall discuss incompatibilism directly and explain why I think it is false. Finally, I shall discuss libertarianism directly, and explain why I think that libertarianism is not only false, but self-contradictory.

All of this crucially depends on my using the correct definition of free will. If my definition of free will is wrong, my whole argument collapses.

Evidential Argument For Soft Determinism

The evidential argument for soft determinism rests on two claims. 1. We have abundant evidence that free will exists and 2. We have abundant evidence that determinism is true. For pretty much all of human history, we have judged each other's behavior. We have over and over again seen people act out of their own decisions, and referred to such actions as “free willed” actions to distinguish them from coerced actions taken against the wills of the actors. In the face of such evidence, it seems absurd (to me, at least) that anyone would ever think that free will doesn't exist. Similarly, for a couple of thousand years, scientists have been discovering the deterministic laws of nature and, because large areas of uncoerced human behavior are also largely predictable, it follows that much, and perhaps all, of free-willed human behavior is also determined.

Remember that, with one absolutely miniscule exception, all of the laws of science rely absolutely on determinism. The one little exception, which concerns certain aspects of quantum mechanics, is limited to certain limited classes of events on the subatomic level. Neurological events, the events, that determine what we think, what we want, and what we do, involve structures made of billions of atoms, so they occur on a scale that is far, far, far, far larger than the subatomic. This means that, as far as anyone can tell, based entirely on all the evidence we have, volitional determinism is true. Whatever happens of the subatomic scale, the human volitional system is deterministic. Since both freewillism and determinism are proven true, it follows that soft determinism is true.

Evidential Argument For Compatibilism

If free will exists, and volitional determinism is true, then it follows that these two are compatible with each other. Since free will does exist, and volitional determinism is true, then compatibilism must be true.

Logical Argument For Compatibilism

The second argument for compatibilism is based on the logical connection between the definitions of free will and determinism. It relies on the fact that the NCFW definition of free will, which I think is clearly the correct definition of free will, actually implies determinism. To see this, think about the fact that the correct definition of free will can be accurately expressed in terms of determinism. You have free will when you determine what you do, and you lack free will when you don't determine what you do. Since free will depends on you causing, making, originating, and in other words determining your own actions, determinism has to be true in your brain for that to be true. In fact, determinism is necessary for free will to exist, and the fact that free will does exist is proof positive that determinism is true.

Opposing Arguments

Now I'm going to review some arguments against soft determinism and compatibilism (Since virtually all of these arguments attack compatibilism, and refuting compatibilism automatically refutes soft determinism, I will lump those two doctrines together as “SDC” for brevity. I think that these are the best opposing arguments out there, but it's always possible that I've made a mistake somewhere, so make sure you read what I say very critically, and think about ways I might have gotten the other side wrong. And, of course, even if I've gotten the other side exactly right, it's always possible that my reply to one of these opposing arguments really fails to refute it.

Opposing Argument One: Determinism Rules Out Free Will

The first and simplest objection to SDC is the statement that determinism rules out free will. This, of course, is the claim that, if an action was determined, then that specific action cannot be a free action or, in other words, it is the statement that compatibilism is false. Normally, we do not count mere statements that the other side is wrong as arguments, but this claim is often made as if it were an argument, so I have decided to deal with it as such.

Incompatibilism

Consider several hundred completely deterministic universes, all of which contain a person called Petra. All of the Petras are exactly the same at this time, and all of the universes are also exactly the same at this time, at least in so far as they concern Petra. (We will call the Petra in the first universe Petra-1, and so on.) At the time of which I write, each Petra is deciding whether or not to have a third glass of apple juice. Because they are all exactly the same, each Petra is at exactly the same point in her decision-making process. In fact, Petra is just about to form her volition, which means she is about to experience the mental event that will make her take, or not take, that glass of apple juice. Because determinism is completely true in all of these universes, and all of the Petras are exactly the same and in exactly the same circumstances, all of them will form exactly the same volition. Let's say they take the drink. Now, the incompatibilist looks at this fact, which is a logical consequence of determinism, and says that because each Petra was determined to do exactly what she did, she could not have done otherwise, and therefore none of the Petras have free will.

But he doesn't actually give a reason for thinking that it works this way. He just assumes that it does.

We do know that none of the Petras would refuse the drink, but because there was nothing there to force any one of then to take the drink, it is still true of each Petra that she could refuse the drink.

None of them would have done otherwise. Every one of them could have done otherwise.

In evaluating the claim that incompatibilism is true, you might want to think about whether determinism sets up the universe so that if Petra had formed the opposite volition, something would have happened to force her to take that drink. The only real way an action can fail to be free willed is for something to close off the other choices. Incompatibilism thus says that if determinism is true, then if we had intervened in one of those universes to make Petra form the opposite volition, to refuse the drink, something would have happened (say a gang of ninjas dropping from the ceiling) to force her to take that drink. If there were no ninjas, or anything else to make Petra take the drink, then she could have done otherwise, if she had chosen to do so. And if she could have done otherwise, had she chosen to do so, then she did take the drink of her own free will.)

You should also notice that nowhere in our textbook does Palmer say how being determined makes an action unfree. If you think that the fact that Petra's own internal state, her hopes, dreams, needs, desires and decisions determines that she will take the drink means that taking the drink was not her free will, then you have to be able to describe a way in which determinism makes free will impossible. After all, we can describe a way in which indeterminism destroys free will by completely cutting a person's actions away from their own thinking. Is there a describable way that determinism does anything to prevent people doing what they decide to do?

If we take this mere claim that compatibilism is false as an argument against compatibilism, and hence against soft determinism, we can also clearly see that it commits the logical fallacy of begging the question. The “argument” claims that compatibilism is false merely because the arguer believes that incompatibilism is true. This is the same as arguing that incompatibilism is true because you believe compatibilism is false. Indeed, it is exactly like someone arguing that incompatibilism is false merely because he believes compatibilism is true.

If you have trouble with the difference between “would” and “could, ”read Escape From Hell Mountain

Since incompatibilism is so frequently assumed to be true by so many people, I have decided to refer to the lack of real logical support for this belief as the “incompatibilism gap.”

Just as the Underpants Gnomes of South Park assume that collecting underpants will somehow lead to profit, the Incompatibilism Gnomes of Libertarianism assume that determinism will somehow rule out free will.

The incompatibilism gap can show up in a variety of ways.

Libertarians could accept that having your actions determined by your volitions does not rule out free will, but assert that having your volitions determined by your immediately preceding state does rule out free will. Thus, for these libertarians, the fact that your volitions are determined by your decisions to act means that your volitions are not free. In this case, the incompatibilism gap shows up between your volitions being determined, and them being unfree. How exactly does a volition being determined make it not free? The libertarians do not say. How could a volition be your volition if it appeared at random, without any connection to your needs, wants, thoughts and decisions? The libertarians do not say.

Alternatively, libertarians could accept that having your volitions determined by your decisions does not rule out free will, but assert that having your decisions determined by your immediately preceding state does rule out free will. Thus, for these libertarians, the fact that your decisions are determined by the combination of your thoughts (both conscious and unconscious), feelings and impulses means that your decisions are not free. In this case, the incompatibilism gap shows up between your decisions being determined, and them being unfree? How exactly does a decision being determined make it not free? The libertarians do not say. How could a decision be your decision if it appeared at random, without any connection to your needs, wants, thoughts and impulses? The libertarians do not say.

And so on, and so on.

Remember, determinism does not say that free will doesn't exist. If someone thinks it implies free will doesn't exist, the will have to explain how you determining what you do, or some state of your mind determining some other state of your mind means that you can't determine what you do. So far, I have not seen any even half-way reasonable argument to bridge the incompatibilism gap, but perhaps one of the following arguments will manage it.

Opposing Argument Two: Freedom Should be Defined as Lack of Cause

This argument attempts to bridge the indeterminism gap by claiming (or assuming) that “freedom” should be defined as “absence of cause” rather than “absent of coercion” or “absence of constraint.” (Above, I refer to this version of free will as IDFW.) Clearly, if libertarians succeed in proving that the concept of “freedom” in our everyday use of the term “free will” is purely defined in terms of lack of cause, they will have definitively refuted SDC. But do we have any reason to define freedom as absence of cause instead of as absence of constraint?

Consider the last time you did something stupid and then took responsibility for it because you did this stupid thing of your own free will. Did you say to yourself, “that action was free-willed because I myself, and nobody else, made me do it” or did you say “that action was free-willed because nothing, not even me myself, made me do it?” Remember, if an action wasn't caused, it couldn't possibly be caused by you, so this definition means that if you do an action because you chose to do it, then that chosen action could not be a free willed action. If you think “freedom” should be defined as “lack of cause, ” then you also think that only actions that you did without deciding to do them can be defined as your free actions. If you think that actions you did because you chose to do them can also be defined as free-willed actions, then you don't think “freedom” should be defined as “lack of cause.” To my mind, this conclusively refutes the claim that “freedom” should be defined as “lack of cause, ” but maybe one of the following arguments will overcome my objection.

Opposing Argument Four: Moral Responsibility Implies that Determinism is False

Personally, the “moral responsibility” objection absolutely mystifies me. I remember a conversation with another philosophy student in which I had just defended soft determinism, with emphasis on evidence for determinism, when the other student came back with “but what about moral responsibility?” as if the existence of moral responsibility were a problem for soft determinism. I asked him what he meant, and he replied that many people thought that moral responsibility existed and that moral responsibility was impossible without free will. I responded that I agreed with this, but I was still wondering why he brought up the subject of moral responsibility. He then said something like, “well they think that if determinism is true then there's no free will, and so no moral responsibility.” I think that my response was to point out that, as I was saying before, determinism does not rule out free will, and so there's no problem.

What worried me about the whole conversation was that this other student seemed to be convinced that invoking the issue of moral responsibility somehow counted as an argument against determinism. The argument seemed to be something like “moral responsibility exists, incompatibilism is true, so determinism is false.” There are three problems here: First, we don't actually have any evidence that moral responsibility exists. Third, we do have tons and tons and tons of evidence that determinism is true. Thus the argument would make more sense in reverse: “determinism is true, incompatibilism is true, so moral responsibility doesn't exist.”

Since most of us either believe in moral responsibility, or would very much like to do so, the idea that determinism rules out moral responsibility is a very scary thought. What makes this even scarier is the fact that we have no evidence that moral responsibility actually exists, while we have tons and tons of proof that volitional determinism is true. If you combine this with the fact that lack of determinism definitely rules out free will, and thus rules out moral responsibility, proving that determinism ruled out moral responsibility would amount to proving that moral responsibility didn't exist. This would be a widely disliked conclusion, but not one that anyone could easily prove wrong, so showing that determinism ruled out moral responsibility would not even begin to prove that determinism was false, even though many people seem to think it would.

Opposing Argument Five: SDC Implies that Moral Responsibility Doesn't Exist

If you read the beginning of the B. F. Skinner section in our text, (217-219, 217-219, or 214-216, section titled “B. F. Skinner”) you will see that both Palmer and Skinner apparently believe that determinism rules out moral responsibility. (This section is more fully discussed in the optional objectsoft.htm.) Here I want you to ignore all the stuff about the “teleological model” and focus entirely on Skinner's reasons for thinking that determinism, which Palmer calls “the causal model”, somehow rules out free will. In fact, as you read this section of the text, I want you to think about one, and only one, question:

Apart from the fact that Skinner thinks that it does, does Palmer give us any reason to think that doing away with the noncausal “teleological” model overturns our moral and legal institutions?

What Palmer and Skinner do here is basically ignore the Incompatibilism Gap, and simply assume that determinism rules out free will. This again commits the fallacy of begging the question, so their argument here fails. Of course, if they manage to bridge that gap, the argument will come back to life again.

Opposing Argument Six: You Should Want What You Don't Want When You Don't Want It.

If someone (call her "Neana") is going to be morally responsible for some action she performs, (such as throwing Neapolitan ice cream at the pope), it must be done of her own free will. Now, for that action to be done of her own free will, it must not only be something she could do, it must also be something she could have avoided doing. (If a gang of Swabian opera singers had kidnapped Neana and fitted her with a mechanical exoskeleton programmed to hurl triple layered gobs of chocolate, strawberry and vanilla ice cream at the nearest pontiff, sneaked her into the Vatican and then let events take their course, that throwing of desserts would not be of her own free will.) Now, compatibilism says that all that is necessary for an action to be free willed is that the actor could have done otherwise if she had wanted to. So, in the case of someone who threw ice cream at the pope because her own deterministic internal decision making processes resulted in her doing so without being forced to by external forces, like ninja, that would be free will, according to compatibilists, because if those deterministic internal forces had determined that she would refrain from pelting the pope, she would have been able to refrain from pelting the pope.

That's not good enough, say the incompatibilists. They point out that if the actor were put in exactly the same situation again (exactly the same frame of mind, exactly the same stomach contents, exactly the same brain state and so on) she would do exactly the same thing. That's the way determinism works. Same past, same future. True, she could do otherwise if she wanted to, but determinism means she won't want to, so she won't do otherwise. Palmer says that "could do otherwise, if she wanted to" is not good enough, because, in order for the actor to have acted freely, she has to be free to want otherwise. This, in Palmer's view, makes determinism rule out free will because, if the actor would want the same thing in the same situation, then she’s not free to want otherwise.

Huh?

Read that crucial sentence on page 231 "Libertarians say that you also have to be free to want differently than you do." This is meant to support the idea that "could do otherwise, if you wanted to" is not logically acceptable as a version of "could do otherwise." I have two comments on this. First, if you insist on "could do otherwise" without the "if you wanted to, " what you get is "could do otherwise whether you wanted to or not." This seems weird to me, since it implies that you can only have free will if you lack control over your own actions. Think about it. You're suffering a deadly attack of some kind of nasty medical thing, and you want to take the pill that will save your life. Say that you take that pill because you want to live. Determinism says that, in the exact same situation, with the exact same knowledge and the exact same feelings, you would do the exact same thing. Compatibilism says that this is fine. Nobody made you take the pill, you acted on your own decision, and so you acted under free will. Compatibilism says the "could have done otherwise" condition is satisfied because you could have done otherwise if you had wanted to. Libertarianism says that this isn't good enough. You have to have been able to otherwise, period. That means that you have to be able to do otherwise, even if you wanted to not do otherwise. That is to say able to do what you don't chose to do. The only way this can make any sense is to say that, according to libertarianism, you can only have free will is if it's possible that, having firmly decided to take the pill, it will happen that, against your own will, you will do something different and thereby endure an agonizing death. This means that, under the libertarian criterion, you only have free will if you don’t control your own actions. Since free will depends on you controlling your own actions, this cannot possibly be true. Since the libertarian version does not make sense, it follows that "could have done otherwise if she had wanted to" is a perfectly cromulent rendition of "could have done otherwise."

My second comment is simply to point out that she was free to want otherwise. No-one forced Neana to want to pelt His Holiness with a combination of strawberry, vanilla and chocolate ice cream. She was perfectly free to want otherwise, she just happened to not want otherwise. It's true that her wanting to pelt the pope was determined by her own (weird) beliefs, needs, desires, thoughts and so on, but that's the way things should be, right? The compatibilist can therefore easily reply to Palmer that Neana could have wanted otherwise, if the want-making mechanism in her brain (her "mind") had made her want otherwise.

Oops.

She could have wanted otherwise, if her want-making mechanism had made her want otherwise. Incompatibilists don't like those "ifs." I can just see a libertarian reaching for his pen to express his dissatisfaction with "could have wanted to do otherwise if her wanting machine had led her to want otherwise." (There's just no pleasing some people.)

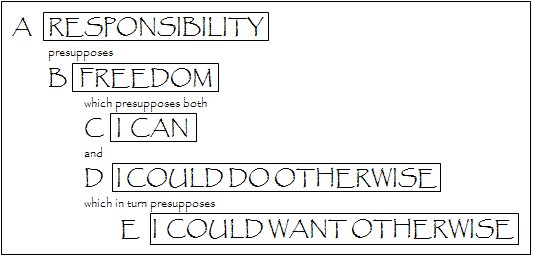

So, what of the idea that you have to be able to (randomly) want to do otherwise? Is this really a problem with "could have done otherwise if she had wanted to?" Given that dropping the "if she had wanted to" doesn't make sense, I don't think so. Rather I think that what Palmer is doing is changing the question after the answer has been given. The diagram on page 231 has changed, as Palmer has added "free to want otherwise" to the criteria for moral responsibility.

Sigh.

So, now we say that being able to do otherwise presupposes being able to want otherwise. Does determinism mean that you're not free to want otherwise what you want? Well, what would "being free to want otherwise" mean? Well it would mean that no external force is there to make you want other than what you want. If whatever it is that makes you wants things was to happen to make you want something different, then you would be able to want that different thing, because nothing would intervene to make you not want that different thing. As far as I can tell, you are free to want differently than you do.

Look at it this way. Do your desires come upon you at random, or do they depend on your preexisting preferences? When you walk into an ice-cream store, does what you want depend on how you feel, what you think and what flavors you like? Or does it happen at random? If you like chocolate and hate cherry, do you find yourself wanting cherry, even if you know you would hate it? Our want-making faculty is deterministic. It comes up with wants for us based on hundreds of factors from our genetics, our physiologies and our histories. Think about everything that has every influenced you, everything that has ever gone into making you the person you are, these are the things that go into the part of you that makes you want what you want. If your want-making system was not deterministic, it would follow that what you want would have absolutely nothing to do with who you are. Randomness is not freedom. Wanting something that has nothing to do with who you are is not freedom. It is, at best, insanity. Determinism does not take away your ability to want other than you do. Indeterminism, on the other hand, would rob you of the ability to want things that make sense based on the person you happen to be.

In our textbook, after repeatedly asserting in various ways that determinism is incompatible with free will, Donald Palmer then states quite clearly that lack of determinism also contradicts free will. This statement appears on page 228 (5th Ed), 231 (4th Ed), and 229, (3rd Ed), *best* and it forms part of his discussion of Werner Heiesenberg's ill-fated attempt to "rescue" free will from determinism by claiming that perhaps human free will is generated by the indeterministic, uncaused events of quantum mechanics. (If you're not sure how lack of determinism would destroy free will, look again at Escape From Hell Mountain.)

Now, one of the oldest known laws of logic is the Law of The Excluded Middle. This law states that, of any proposition, either it is true or it's negation is true. For instance, either it is true that 2+4=7 or it is not true that 2+4=7. It is not logically possible for a proposition and it's negation to be both false at the same time. From this is follows that, as a matter of logic, it is absolutely impossible for volitional determinism and volitional indeterminism to be both false since volitional indeterminism is nothing other than the negation of volitional determinism.

If we take logic at all seriously, to assert that both determinism and indeterminism rule out free will is to assert that hard determinism is true. This is a matter of deductive logic where, if something is proved, it is proved with absolute certainty. If we combine determinism ruling out free will with indeterminism ruling out free will, we get a valid deductive argument whose conclusion is that free will doesn't exist.

In symbols, this argument would look like this:

D![]() ~F

~F

~D ~F

~F

~F

If determinism is true, free will is false.

If determinism is not true, free will is false.

Free will is false.

To say that this is a valid argument is to say that if both premises are true, then the conclusion cannot be false. (If you're interested in such things, a proof of this argument would involve the principle of bivalence, constructive dilemma and tautology.)

Palmer, however, does not seem to agree with this analysis. Immediately after showing clearly how indeterminism would wipe out free will, he immediately asserts that "freedom may very well be considered the opposite of necessity. Yet there are not just two components of this formula but three, " and puts in a little diagram (which you will see later) to illustrate this claim.

There are two senses of the word "necessity, " and I think that Palmer is confusing them with each other. There is "necessity" in the sense of determinism, and there is "necessity" in the sense of constraint. This is a vitally important distinction because where constraint clearly eliminates free will, it is not at all clear that determinism has any negative effect on freedom.