rename me

The Libertarian FallacyYou don't have to actually read our textbook for this unit. There's so much in it that's wrong that I'm not sure that reading it wouldn't do more harm than good. Still, you deserve to hear the other side in this debate, so I've included optional reading assignments in this chapter which will allow you to see what Palmer says about some of the claims I make in this chapter.

If you're pressed for time, you could concentrate of finding

answers to the following questions:

1. What are the main claims of libertarianism?

2. What are the main claims of soft determinism?

3. What are the main claims of hard determinism?

4. What is the NCFW definition of free will?

5. What is the IDFW definition of free will?

6. What is the basic argument for soft determinism?

7. What is the basic argument for compatibilism?

8. What is the "incompatibilism gap?"

9. What is wrong with defining freedom as "lack of cause?"

10. What is wrong with using moral responsibility to argue against

determinism?

11. What is the "could do otherwise" argument against soft determinism?

12. What is wrong with the "could do otherwise" argument against soft

determinism?

13. How does libertarianism contradict itself?

I call this chapter “The Libertarian Fallacy” because I believe that the doctrine Palmer calls “Libertarianism” is based on logically fallacious reasoning. Hopefully, the logical properties of Libertarianism will emerge as you study the reading. (The doctrine called “libertarianism” in this chapter has nothing to do with the ethical and political doctrines that are also called “libertarianism.”)

Two Definitions of Free WillPeople interested in this topic often disagree about the nature of free will. They offer and defend their own favored definitions, and sometimes accuse each other of implicitly using irrational definitions of free will, so it very is important to be as clear as possible about what exactly is meant by “free will” in any given sentence.

Soft determinists define “free will” as a condition in which a person determines her own actions. If a person is prevented from doing what she wants to do, and is instead made to do something she did not personally decide to do, then that action wasn't free-willed, according to soft determinism. (I call this “Non-Coercion Free Will, ” or “NCFW”.) This is the definition of “free will” I use in this reading. When I write “free will, ” I will mean NCFW.

Libertarians sometimes appear to define “free will” as a condition in which a person's actions are not determined by anything. If a person's action is determined by some part of the present state of the universe, whether it be ninja, clowns, a crack panzer division of the Waffen SS, or her own personal preferences, thinking and choices, then that action wasn't free-willed, according to libertarianism. (I call this the “In-Determinism Free Will, ” or “IDFW”.) While I occasionally discuss IDFW, it is never what I mean when I write “free will.”

I derive the IDFW definition from Palmer's comments about free will in the text book. I don't claim that it makes sense, only that it is my best guess at to what Libertarians sometimes think. If you can find anything Palmer says about free will that suggests a different definition of “free will” for libertarianism, I'd be interested to hear about it.

Other incompatibilists, such as hard determinists appear to also define free will as IDFW, so I'm only going to worry about NCFW and IDFW in this unit. I basically see this debate as a three-way fight between libertarianism, soft determinism and hard determinism.

Ground Rules

For my money, there are some key questions here.

1. Which definition of free will is correct?

2. Based on the correct definition of free will, is

incompatibilism true?

3. Based on the correct definition of free will, is

free will compatible with indeterminism ?

Based on these questions, I think the can define the following victory conditions for the dogs in this fight:

V1. If the incompatibilists (libertarians and hard determinists) can prove that the IDFW definition of free will is correct, then they will have proved that incompatibilism is true, that free will is compatible with indeterminism (and that soft determinism is false).

V2. If the libertarians can prove IDFW is correct, and that free will (by that definition) actually exists, then they will have proved that incompatibilism is true, that free will is compatible with indeterminism, that both soft and hard determinism are false, and that libertarianism is true.

V3. If the libertarians can't prove IDFW is correct, but can prove that incompatibilism is true, then they will have proved that soft determinism is false and that either hard determinism or libertarianism is true.

V3. If the libertarians can't prove IDFW is correct, but can prove that incompatibilism is true, and that free will (by whatever definition is correct) actually exists, then they will have proved that both soft and hard determinism are false, and that libertarianism is true.

V4. If the hard determinists can prove IDFW is correct, and that determinism is true, then they will have proved that incompatibilism is true, that both libertarianism and soft determinism are false, and that hard determinism is true.

V5. If the soft determinists can prove that determinism is true, and that free will (by whatever definition is correct) actually exists, then they will have proved that both compatibilism and soft determinism are true, and that both libertarianism and hard determinism are false,

V6. If the soft determinists can prove that NCFW is correct, and that free will (by that definition) actually exists, then the soft determinists will have proven that compatibilism is true.

V7. If the soft determinists can prove that determinism is true, that NCFW is correct, and that free will (by that definition) actually exists, then the soft determinists will have proven that both compatibilism and soft determinism are true.

V8. If the incompatibilists (libertarians and hard determinists) can prove that volitional indeterminism (the doctrine that human volitions are randomly generated, or just randomly appear from nowhere) is true, then they will have proven that soft determinism is false.

V9. If the libertarians can prove that volitional indeterminism is true, and that free will (by whatever definition is correct) actually exists, then they will have proven that soft and hard determinism are both false and that libertarianism is true.

The Plan

My plan for the rest of this unit is as follows: First, I shall give the basic arguments for soft determinism and compatibilism (which I think are the correct theories). Second, I shall discuss what I take to be the most strongest objections to soft determinism (starting with the easiest) and, in each case, tell you why I think that the objection fails to refute soft determinism. (Additional objections will be available in optional reading.) Third, I shall discuss incompatibilism directly and explain why I think it is false. Finally, I shall discuss libertarianism directly, and explain why I think that libertarianism is not only false, but self-contradictory.

All of this crucially depends on my using the correct definition of free will. If my definition of free will is wrong, my whole argument collapses.

Evidential Argument For Soft Determinism

The evidential argument for soft determinism rests on two claims. 1. We have abundant evidence that free will exists and 2. We have abundant evidence that determinism is true. For pretty much all of human history, we have judged each other's behavior. We have over and over again seen people act out of their own decisions, and referred to such actions as “free willed” actions to distinguish them from coerced actions taken against the wills of the actors. In the face of such evidence, it seems absurd (to me, at least) that anyone would ever think that free will doesn't exist. Similarly, for a couple of thousand years, scientists have been discovering the deterministic laws of nature and, because large areas of uncoerced human behavior are also largely predictable, it follows that much, and perhaps all, of free-willed human behavior is also determined.

Remember that, with one absolutely miniscule exception, all of the laws of science rely absolutely on determinism. The one little exception, which concerns certain aspects of quantum mechanics, is limited to certain limited classes of events on the subatomic level. Neurological events, the events, that determine what we think, what we want, and what we do, involve structures made of billions of atoms, so they occur on a scale that is far, far, far, far larger than the subatomic. This means that, as far as anyone can tell, based entirely on all the evidence we have, volitional determinism is true. Whatever happens of the subatomic scale, the human volitional system is deterministic. Since both freewillism and determinism are proven true, it follows that soft determinism is true.

Evidential Argument For Compatibilism

If free will exists, and volitional determinism is true, then it follows that these two are compatible with each other. Since free will does exist, and volitional determinism is true, then compatibilism must be true.

Logical Argument For Compatibilism

The second argument for compatibilism is based on the logical connection between the definitions of free will and determinism. It relies on the fact that the NCFW definition of free will, which I think is clearly the correct definition of free will, actually implies determinism. To see this, think about the fact that the correct definition of free will can be accurately expressed in terms of determinism. You have free will when you determine what you do, and you lack free will when you don't determine what you do. Since free will depends on you causing, making, originating, and in other words determining your own actions, determinism has to be true in your brain for that to be true. In fact, determinism is necessary for free will to exist, and the fact that free will does exist is proof positive that determinism is true.

Opposing Arguments

Now I'm going to review some arguments against soft determinism and compatibilism (Since virtually all of these arguments attack compatibilism, and refuting compatibilism automatically refutes soft determinism, I will lump those two doctrines together as “SDC” for brevity. I think that these are the best opposing arguments out there, but it's always possible that I've made a mistake somewhere, so make sure you read what I say very critically, and think about ways I might have gotten the other side wrong. And, of course, even if I've gotten the other side exactly right, it's always possible that my reply to one of these opposing arguments really fails to refute it.

Opposing Argument One: Determinism Rules Out Free Will

The first and simplest objection to SDC is the statement that determinism rules out free will. This, of course, is the claim that, if an action was determined, then that specific action cannot be a free action or, in other words, it is the statement that compatibilism is false. Normally, we do not count mere statements that the other side is wrong as arguments, but this claim is often made as if it were an argument, so I have decided to deal with it as such.

Incompatibilism

Consider several hundred completely deterministic universes, all of which contain a person called Petra. All of the Petras are exactly the same at this time, and all of the universes are also exactly the same at this time, at least in so far as they concern Petra. (We will call the Petra in the first universe Petra-1, and so on.) At the time of which I write, each Petra is deciding whether or not to have a third glass of apple juice. Because they are all exactly the same, each Petra is at exactly the same point in her decision-making process. In fact, Petra is just about to form her volition, which means she is about to experience the mental event that will make her take, or not take, that glass of apple juice. Because determinism is completely true in all of these universes, and all of the Petras are exactly the same and in exactly the same circumstances, all of them will form exactly the same volition. Let's say they take the drink. Now, the incompatibilist looks at this fact, which is a logical consequence of determinism, and says that because each Petra was determined to do exactly what she did, she could not have done otherwise, and therefore none of the Petras have free will.

But he doesn't actually give a reason for thinking that it works this way. He just assumes that it does.

We do know that none of the Petras would refuse the drink, but because there was nothing there to force any one of then to take the drink, it is still true of each Petra that she could refuse the drink.

None of them would have done otherwise. Every one of them could have done otherwise.

In evaluating the claim that incompatibilism is true, you might want to think about whether determinism sets up the universe so that if Petra had formed the opposite volition, something would have happened to force her to take that drink. The only real way an action can fail to be free willed is for something to close off the other choices. Incompatibilism thus says that if determinism is true, then if we had intervened in one of those universes to make Petra form the opposite volition, to refuse the drink, something would have happened (say a gang of ninjas dropping from the ceiling) to force her to take that drink. If there were no ninjas, or anything else to make Petra take the drink, then she could have done otherwise, if she had chosen to do so. And if she could have done otherwise, had she chosen to do so, then she did take the drink of her own free will.)

If you think that the fact that Petra's own internal state, her hopes, dreams, needs, desires and decisions determines that she will take the drink means that taking the drink was not her free will, then you have to be able to describe a way in which determinism makes free will impossible. After all, we can describe a way in which indeterminism destroys free will by completely cutting a person's actions away from their own thinking. Is there a describable way that determinism does anything to prevent people doing what they decide to do?

If we take this mere claim that compatibilism is false as an argument against compatibilism, and hence against soft determinism, we can also clearly see that it commits the logical fallacy of begging the question. The “argument” claims that compatibilism is false merely because the arguer believes that incompatibilism is true. This is the same as arguing that incompatibilism is true because you believe compatibilism is false. Indeed, it is exactly like someone arguing that incompatibilism is false merely because he believes compatibilism is true.

If you have trouble with the difference between “would” and “could, ”read Escape From Hell Mountain

Since incompatibilism is so frequently assumed to be true by so many people, I have decided to refer to the lack of real logical support for this belief as the “incompatibilism gap.”

Just as the Underpants Gnomes of South Park assume that collecting underpants will somehow lead to profit, the Incompatibilism Gnomes of Libertarianism assume that determinism will somehow rule out free will.

The incompatibilism gap can show up in a variety of ways.

Libertarians could accept that having your actions determined by your volitions does not rule out free will, but assert that having your volitions determined by your immediately preceding state does rule out free will. Thus, for these libertarians, the fact that your volitions are determined by your decisions to act means that your volitions are not free. In this case, the incompatibilism gap shows up between your volitions being determined, and them being unfree. How exactly does a volition being determined make it not free? The libertarians do not say. How could a volition be your volition if it appeared at random, without any connection to your needs, wants, thoughts and decisions? The libertarians do not say.

Alternatively, libertarians could accept that having your volitions determined by your decisions does not rule out free will, but assert that having your decisions determined by your immediately preceding state does rule out free will. Thus, for these libertarians, the fact that your decisions are determined by the combination of your thoughts (both conscious and unconscious), feelings and impulses means that your decisions are not free. In this case, the incompatibilism gap shows up between your decisions being determined, and them being unfree? How exactly does a decision being determined make it not free? The libertarians do not say. How could a decision be your decision if it appeared at random, without any connection to your needs, wants, thoughts and impulses? The libertarians do not say.

And so on, and so on.

Remember, determinism does not say that free will doesn't exist. If someone thinks it implies free will doesn't exist, the will have to explain how you determining what you do, or some state of your mind determining some other state of your mind means that you can't determine what you do. So far, I have not seen any even half-way reasonable argument to bridge the incompatibilism gap, but perhaps one of the following arguments will manage it.

Opposing Argument Two: Freedom Should be Defined as Lack of Cause

This argument attempts to bridge the indeterminism gap by claiming (or assuming) that “freedom” should be defined as “absence of cause” rather than “absent of coercion” or “absence of constraint.” (Above, I refer to this version of free will as IDFW.) Clearly, if libertarians succeed in proving that the concept of “freedom” in our everyday use of the term “free will” is purely defined in terms of lack of cause, they will have definitively refuted SDC. But do we have any reason to define freedom as absence of cause instead of as absence of constraint?

Consider the last time you did something stupid and then took responsibility for it because you did this stupid thing of your own free will. Did you say to yourself, “that action was free-willed because I myself, and nobody else, made me do it” or did you say “that action was free-willed because nothing, not even me myself, made me do it?” Remember, if an action wasn't caused, it couldn't possibly be caused by you, so this definition means that if you do an action because you chose to do it, then that chosen action could not be a free willed action. If you think “freedom” should be defined as “lack of cause, ” then you also think that only actions that you did without deciding to do them can be defined as your free actions. If you think that actions you did because you chose to do them can also be defined as free-willed actions, then you don't think “freedom” should be defined as “lack of cause.” To my mind, this conclusively refutes the claim that “freedom” should be defined as “lack of cause, ” but maybe one of the following arguments will overcome my objection.

Opposing Argument Four: Moral Responsibility Implies that Determinism is False

Personally, the “moral responsibility” objection absolutely mystifies me. I remember a conversation with another philosophy student in which I had just defended soft determinism, with emphasis on evidence for determinism, when the other student came back with “but what about moral responsibility?” as if the existence of moral responsibility were a problem for soft determinism. I asked him what he meant, and he replied that many people thought that moral responsibility existed and that moral responsibility was impossible without free will. I responded that I agreed with this, but I was still wondering why he brought up the subject of moral responsibility. He then said something like, “well they think that if determinism is true then there's no free will, and so no moral responsibility.” I think that my response was to point out that, as I was saying before, determinism does not rule out free will, and so there's no problem.

What worried me about the whole conversation was that this other student seemed to be convinced that invoking the issue of moral responsibility somehow counted as an argument against determinism. The argument seemed to be something like “moral responsibility exists, incompatibilism is true, so determinism is false.” There are three problems here: First, we don't actually have any evidence that moral responsibility exists. Third, we do have tons and tons and tons of evidence that determinism is true. Thus the argument would make more sense in reverse: “determinism is true, incompatibilism is true, so moral responsibility doesn't exist.”

Since most of us either believe in moral responsibility, or would very much like to do so, the idea that determinism rules out moral responsibility is a very scary thought. What makes this even scarier is the fact that we have no evidence that moral responsibility actually exists, while we have tons and tons of proof that volitional determinism is true. If you combine this with the fact that lack of determinism definitely rules out free will, and thus rules out moral responsibility, proving that determinism ruled out moral responsibility would amount to proving that moral responsibility didn't exist. This would be a widely disliked conclusion, but not one that anyone could easily prove wrong, so showing that determinism ruled out moral responsibility would not even begin to prove that determinism was false, even though many people seem to think it would.

Opposing Argument Five: SDC Implies that Moral Responsibility Doesn't Exist

If you read the beginning of the B. F. Skinner section in our text, (217-219, 217-219, or 214-216, section titled “B. F. Skinner”) you will see that both Palmer and Skinner apparently believe that determinism rules out moral responsibility. (This section is more fully discussed in the optional objectsoft.htm.) Here I want you to ignore all the stuff about the “teleological model” and focus entirely on Skinner's reasons for thinking that determinism, which Palmer calls “the causal model”, somehow rules out free will. In fact, as you read this section of the text, I want you to think about one, and only one, question:

Apart from the fact that Skinner thinks that it does, does Palmer give us any reason to think that doing away with the noncausal “teleological” model overturns our moral and legal institutions?

What Palmer and Skinner do here is basically ignore the Incompatibilism Gap, and simply assume that determinism rules out free will. This again commits the fallacy of begging the question, so their argument here fails. Of course, if they manage to bridge that gap, the argument will come back to life again.

Opposing Argument Six: You Should Want What You Don't Want When You Don't Want It.

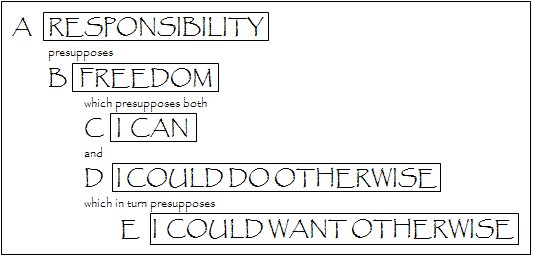

If someone (call her "Neana") is going to be morally responsible for some action she performs, (such as throwing Neapolitan ice cream at the pope), it must be done of her own free will. Now, for that action to be done of her own free will, it must not only be something she could do, it must also be something she could have avoided doing. (If a gang of Swabian opera singers had kidnapped Neana and fitted her with a mechanical exoskeleton programmed to hurl triple layered gobs of chocolate, strawberry and vanilla ice cream at the nearest pontiff, sneaked her into the Vatican and then let events take their course, that throwing of desserts would not be of her own free will.) Now, compatibilism says that all that is necessary for an action to be free willed is that the actor could have done otherwise if she had wanted to. So, in the case of someone who threw ice cream at the pope because her own deterministic internal decision making processes resulted in her doing so without being forced to by external forces, like ninja, that would be free will, according to compatibilists, because if those deterministic internal forces had determined that she would refrain from pelting the pope, she would have been able to refrain from pelting the pope.

That's not good enough, say the incompatibilists. They point out that if the actor were put in exactly the same situation again (exactly the same frame of mind, exactly the same stomach contents, exactly the same brain state and so on) she would do exactly the same thing. That's the way determinism works. Same past, same future. True, she could do otherwise if she wanted to, but determinism means she won't want to, so she won't do otherwise. Palmer says that "could do otherwise, if she wanted to" is not good enough, because, in order for the actor to have acted freely, she has to be free to want otherwise. This, in Palmer's view, makes determinism rule out free will because, if the actor would want the same thing in the same situation, then she’s not free to want otherwise.

Huh?

Read that crucial sentence on page 231 "Libertarians say that you also have to be free to want differently than you do." This is meant to support the idea that "could do otherwise, if you wanted to" is not logically acceptable as a version of "could do otherwise." I have two comments on this. First, if you insist on "could do otherwise" without the "if you wanted to, " what you get is "could do otherwise whether you wanted to or not." This seems weird to me, since it implies that you can only have free will if you lack control over your own actions. Think about it. You're suffering a deadly attack of some kind of nasty medical thing, and you want to take the pill that will save your life. Say that you take that pill because you want to live. Determinism says that, in the exact same situation, with the exact same knowledge and the exact same feelings, you would do the exact same thing. Compatibilism says that this is fine. Nobody made you take the pill, you acted on your own decision, and so you acted under free will. Compatibilism says the "could have done otherwise" condition is satisfied because you could have done otherwise if you had wanted to. Libertarianism says that this isn't good enough. You have to have been able to otherwise, period. That means that you have to be able to do otherwise, even if you wanted to not do otherwise. That is to say able to do what you don't chose to do. The only way this can make any sense is to say that, according to libertarianism, you can only have free will is if it's possible that, having firmly decided to take the pill, it will happen that, against your own will, you will do something different and thereby endure an agonizing death. This means that, under the libertarian criterion, you only have free will if you don’t control your own actions. Since free will depends on you controlling your own actions, this cannot possibly be true. Since the libertarian version does not make sense, it follows that "could have done otherwise if she had wanted to" is a perfectly cromulent rendition of "could have done otherwise."

My second comment is simply to point out that she was free to want otherwise. No-one forced Neana to want to pelt His Holiness with a combination of strawberry, vanilla and chocolate ice cream. She was perfectly free to want otherwise, she just happened to not want otherwise. It's true that her wanting to pelt the pope was determined by her own (weird) beliefs, needs, desires, thoughts and so on, but that's the way things should be, right? The compatibilist can therefore easily reply to Palmer that Neana could have wanted otherwise, if the want-making mechanism in her brain (her "mind") had made her want otherwise.

Oops.

She could have wanted otherwise, if her want-making mechanism had made her want otherwise. Incompatibilists don't like those "ifs." I can just see a libertarian reaching for his pen to express his dissatisfaction with "could have wanted to do otherwise if her wanting machine had led her to want otherwise." (There's just no pleasing some people.)

So, what of the idea that you have to be able to (randomly) want to do otherwise? Is this really a problem with "could have done otherwise if she had wanted to?" Given that dropping the "if she had wanted to" doesn't make sense, I don't think so. Rather I think that what Palmer is doing is changing the question after the answer has been given. The diagram on page 231 has changed, as Palmer has added "free to want otherwise" to the criteria for moral responsibility.

Sigh.

So, now we say that being able to do otherwise presupposes being able to want otherwise. Does determinism mean that you're not free to want otherwise what you want? Well, what would "being free to want otherwise" mean? Well it would mean that no external force is there to make you want other than what you want. If whatever it is that makes you wants things was to happen to make you want something different, then you would be able to want that different thing, because nothing would intervene to make you not want that different thing. As far as I can tell, you are free to want differently than you do.

Look at it this way. Do your desires come upon you at random, or do they depend on your preexisting preferences? When you walk into an ice-cream store, does what you want depend on how you feel, what you think and what flavors you like? Or does it happen at random? If you like chocolate and hate cherry, do you find yourself wanting cherry, even if you know you would hate it? Our want-making faculty is deterministic. It comes up with wants for us based on hundreds of factors from our genetics, our physiologies and our histories. Think about everything that has every influenced you, everything that has ever gone into making you the person you are, these are the things that go into the part of you that makes you want what you want. If your want-making system was not deterministic, it would follow that what you want would have absolutely nothing to do with who you are. Randomness is not freedom. Wanting something that has nothing to do with who you are is not freedom. It is, at best, insanity. Determinism does not take away your ability to want other than you do. Indeterminism, on the other hand, would rob you of the ability to want things that make sense based on the person you happen to be.

In our textbook, after repeatedly asserting in various ways that determinism is incompatible with free will, Donald Palmer then states quite clearly that lack of determinism also contradicts free will. This statement appears on page 228 (5th Ed), 231 (4th Ed), and 229, (3rd Ed), *best* and it forms part of his discussion of Werner Heiesenberg's ill-fated attempt to "rescue" free will from determinism by claiming that perhaps human free will is generated by the indeterministic, uncaused events of quantum mechanics. (If you're not sure how lack of determinism would destroy free will, look again at Escape From Hell Mountain.)

Now, one of the oldest known laws of logic is the Law of The Excluded Middle. This law states that, of any proposition, either it is true or it's negation is true. For instance, either it is true that 2+4=7 or it is not true that 2+4=7. It is not logically possible for a proposition and it's negation to be both false at the same time. From this is follows that, as a matter of logic, it is absolutely impossible for volitional determinism and volitional indeterminism to be both false since volitional indeterminism is nothing other than the negation of volitional determinism.

If we take logic at all seriously, to assert that both determinism and indeterminism rule out free will is to assert that hard determinism is true. This is a matter of deductive logic where, if something is proved, it is proved with absolute certainty. If we combine determinism ruling out free will with indeterminism ruling out free will, we get a valid deductive argument whose conclusion is that free will doesn't exist.

In symbols, this argument would look like this:

D![]() ~F

~F

~D ~F

~F

~F

If determinism is true, free will is false.

If determinism is not true, free will is false.

Free will is false.

To say that this is a valid argument is to say that if both premises are true, then the conclusion cannot be false. (If you're interested in such things, a proof of this argument would involve the principle of bivalence, constructive dilemma and tautology.)

Palmer, however, does not seem to agree with this analysis. Immediately after showing clearly how indeterminism would wipe out free will, he immediately asserts that "freedom may very well be considered the opposite of necessity. Yet there are not just two components of this formula but three, " and puts in a little diagram (which you will see later) to illustrate this claim.

There are two senses of the word "necessity, " and I think that Palmer is confusing them with each other. There is "necessity" in the sense of determinism, and there is "necessity" in the sense of constraint. This is a vitally important distinction because where constraint clearly eliminates free will, it is not at all clear that determinism has any negative effect on freedom.

Consider Nescon and Nesdet. They are not related to each other, but by a strange coincidence, each of them finds herself pouring a saucepan full of lukewarm Bird's Custard. into a box of kittens, making those kittens sticky and unhappy. The difference between these two custardings is that Nescon poured in the custard because an unstoppable alien armada, equipped with unspeakably powerful weapons told her, quite truthfully, that they would destroy her, the whole rest of the planet, and several nearby planets, if she did not custard the kittens. Nesdet just did it because she has a mean sense of humor, and doesn't like kittens. In both cases the custarding was "necessary" in the sense of being determined, because in neither case was it a random (undetermined) act. But only in the case of Nescon was it a "necessary" act in the sense of being constrained. Because of the alien threat to destroy the world, she found it necessary to custard the kittens. In the case of Nesdet, who custarded the kittens because she wanted to, that action was only "necessary" in the sense of being determined. It was not "necessary" in the sense of being coerced, and so it was a free act, even though it was "necessary" in the sense of being determined. Thus, if we take "necessity" to strictly mean "determinism, " as Palmer does throughout our text, it is clear that "necessity" is not the opposite of freedom. And it seems to me that to assert that necessity is the opposite of freedom in this context is to swim perilously close to the fallacy of equivocation.

In addition to stating (falsely) that necessity (in the sense of "determinism") is the opposite of freedom, Palmer also says that "there are not just two components of this formula but three" (228 (5th Ed), 231 (4th Ed), 229, (3rd Ed)) and illustrates this claim with a little diagram of a triangle whose vertices are marked "necessity, " "randomness" and "freedom." Given that the diagram is supposed to indicate that our choices are not limited to determinism and the lack thereof, I have reproduced the diagram below, both in it's original wording, and (on the right) with the vertex titles translated into appropriate and unambiguous terms.

|

|

|

How did I come up with these translations? Well, Palmer is arguing for libertarianism and incompatibilism, he seems convinced that determinism rules out free will, he keeps referring to determinism as "necessity" and, as far as I can tell, never even uses the words "coercion" and "constraint, " so I have to assume that he means "necessity" in the sense of determinism. Besides, if he was taking "necessity" to mean "constraint" or "coercion, " he would not be arguing against soft determinism! So I'm pretty confident that "necessity" here means "determinism."

As for "randomness" meaning "indeterminism, " well, although there is a sense of "randomness" that means "unpredictability" instead of "indeterminism, " this diagram is about opposites, so while unpredictability is definitely not the opposite of determinism, "indeterminism"is just a word meaning "not determinism, " so I'm pretty confident here too.

But what does "freedom" mean in this diagram ? It can't mean "absence of constraint" here because absence of constraint is not the opposite of either determinism or indeterminism, and if Palmer defined "freedom" as "absence of constraint, " he would have absolutely no argument against soft determinism, so our only alternative here is to take "freedom" as the negation of both the other vertices of this diagram, which means that it stands for the combination of not determinism and not indeterminism. So in this diagram, the word "freedom" means "not determinism and not not determinism, " and that violates the Law of The Excluded Middle.

If you're not sure you understand this, answer the following questions for that particular reading.

Questions for pages 228

(the "three component" formula and the triangle diagram)

These questions concern only two sentences

undone diagram.

What does "necessity" mean?

What may necessity be considered the opposite of?

How many components are there in this formula?

What component of the diagram corresponds to determinism?

What component of the diagram corresponds to indeterminism?

What does the other component correspond to?

Does Palmer give an example of a system that is governed by neither

necessity nor randomness?

Does he give any explanation of what he means by the word "freedom" in

this particular context?

(Stuff that he said about other usages of

"freedom, " only count if they give examples of systems that are

provably neither deterministic nor indeterministic.)

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between necessity and determinism?

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between randomness and indeterminism?

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between indeterminism and lack of determinism?

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between necessity and lack of randomness?

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between randomness and lack of necessity?

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between determinism and lack of randomness?

In the terms of this class, is there any

difference between indeterminism and lack of necessity?

In the three part diagram "freedom" is not "necessity, " so is it

therefore the same as lack of necessity?

Is lack of necessity different from randomness? (Be honest.)

In the three part diagram "freedom" is not "randomness, " so is it

therefore the same as lack of randomness?

Is lack of randomness different from necessity? (Be honest.)

In terms of determinism and indeterminism, what is "freedom" in this

diagram?

Is it logically possible for something to be both not determinist and

not not determinist?

Is it logically possible for something to be both not random and not

not random?

Is it logically possible for something to be both not necessary and not

not necessary?

Is it logically possible for there to be a third

state that is both not randomness and

not necessity?

Now look again at the two basic claims of libertarianism:

L1. Free will

exists, and

L2. Volitional Determinism is false.

At this point in the discussion, you may be ready to understand why I claim that these two propositions contradict each other. That's right, I claim that to say that free will exists is to imply that determinism is true, and to say that determinism is false is to imply that free will does not exist. I think the correct definition of free will

The idea that the idea of free will without determinism contradicts itself is the basic point of the Dr. Evertight example in our text, (220 (5th Ed), and 223 (4th Ed)). Where soft determinists see free actions as unconstrained actions, libertarians see free actions as uncaused actions. Look at Joe and Dr. Evertight. On a soft deterministic view, if Joe calls Dr. Evertight because he has decided to, that's a free action because nobody made him do it and, if he had wanted to do otherwise, he could have done otherwise. He was also free to want otherwise. No outside force made him want what he wanted, so if his own desires, preferences and reasoning had added up differently, he would have wanted differently. On a libertarian view, if Joe calls Dr. Evertight because he has decided to, that's not a free action because he caused himself to do it and, given that he had firmly decided to do it and did not change his mind, he would not do otherwise. For libertarians, free will only exists if people's decisions do not determine what they do. So if a person decides to do something and does not change his mind before the moment of action, that action will only be free if it's possible that the actor will do any one of an infinite number of possible actions that have nothing to do with the decision. In the Dr. Evertight example, libertarianism implies that Joe's action is only free if based on his firm and single minded intention to call Dr. Evertight, it's still possible that, without changing his mind, he does not call Dr. Evertight, despite his absolute best efforts to control his own destiny and do so. The philosophers who oppose libertarianism believe that the whole point of free will is to at least somewhat control your own destiny, and boggle at the idea of a definition of "freedom" that absolutely rules out the possibility of self-control. Some philosophers, including myself, but probably not including Donald Palmer, believe that the idea that free actions have to be uncaused makes absolutely no sense. That's right, I, and at least some other people believe that free will requires determinism, and that libertarianism contradicts itself, and thus makes no sense whatsoever.

Let me illustrate this by stating the two basic claims of libertarianism in terms that rule out all ambiguity:

L1. People's

internal states sometimes determine their own actions,

L2. People's internal states never determine their own actions.

The definition of free will logically has to include determinism at every step of the process by which a free action comes about. Your actions have to be determined by your volitions, your volitions have to be determined by your decisions, your decisions have to be determined by your thinking, your thinking has to be determined by your beliefs, feelings, hopes, fears, desires and needs at that time. If any part of your thinking is not determined by whatever mental state preceded it, then it was not determined by you and can hardly be counted as your thinking.

To say that an action occurred of your own free will is to say that something about you, your present combination of desires, hopes, dreams, beliefs, intentions determined that you would have the volition to do that act, and that no external force prevented your volition from determining that you did that act. If determinism is false. or even if only volitional determinism is false, it's not possible for anything about you to ever determine what you do, so lack of determinism would actually make free will impossible, and libertarianism therefore directly contradicts itself!

So there!

Possible Quiz Questions:

1. What are the main

claims of libertarianism?

2. What are the main claims of soft determinism?

3. What are the main claims of hard determinism?

4. What is the NCFW definition of free will?

5. What is the IDFW definition of free will?

6. What is the basic argument for soft determinism?

7. What is the basic argument for compatibilism?

8. What is the "incompatibilism gap?"

9. What is wrong with defining freedom as "lack of cause?"

10. What is wrong with using moral responsibility to argue against

determinism?

11. What is the "could do otherwise" argument against soft determinism?

12. What is wrong with the "could do otherwise" argument against soft

determinism?

13. How does libertarianism contradict itself?

Explain and

analyze the NCFW and IDFW definitions of free will.

What do "NCFW" and "IDFW" stand for? How does NCFW define free will?

How does IDFW define free will? What does the word "free" mean for

NCFW? What does the word "free" mean for IDFW? Give an example of an

action that is free-willed according to NCFW but not according to IDFW.

Give an example of an action that is free-willed according to IDFW but

not according to NCFW. What reasons do we have to think that NCFW is

correct? Without assuming incompatibilism, do we

have any reason to think that IDFW is correct? If so, what is that

reason? What reason(s) do we have to think that IDFW cannot be correct?

Explain and analyze incompatibilism and the Incompatibilism Gap. Clearly and completely explain the doctrine of incompatibilism and illustrate it with at least one example that, according to incompatibilism, shows determinism ruling out free will. Explain the "incompatibilism gap," and explain how it is supposed to be a problem for incompatibilism. Finally explain one or more attempts to bridge the gap, say how well it bridges the gap, and explain your answer.

Analyze the relationship between moral responsibility and free will. Explain B. F. Skinner's argument against moral responsibility. Explain the moral responsibility argument against free will. Say what assumption both arguments have in common. Say what one argument has and the other argument doesn't, why this is important, and which argument ends up being the stronger because of it. Finally, if that common assumption is true, what are its logical consequences for moral responsibility or determinism?

Analyze Palmer's

criticism of the compatibilist's

analysis of "could have done otherwise."

How do compatibilists interpret the phrase "she could have done

otherwise?" Do incompatibilists agree with this interpretation? How do

incompatibilists (apparently) think this phrase should be

interpreted? What additional condition (E.) do

incompatibilists add to the "A: moral

responsibility presupposes B: freedom, freedom presupposes C. I can and

D. I could do otherwise" diagram. Do incompatibilists prove that

determinism means that people are not free to want

things that are different from the things they happen to want? Explain

this objection and your analysis of it anyway you can.

Explain why libertarianism actually contradicts itself.

Describe and analyze Donald Palmer's "Necessity, Randomness, Freedom"

response to the fact that lack of determinism rules out free will. What

is "necessity" in this model? What is "randomness" in this model? What

is "freedom" in this model? If we interpret this model as referring to

the presence and absence of determinism, what logical rule(s) does this

model violate? Why doesn't this model save libertarianism from the

indeterminism problem? Give the most precise definitions of free will

and determinism, and explain what the correct definition of free will

implies about determinism. Finally explain exactly why libertarianism

contradicts itself.

Any exam answer can be enhanced by addition of any comments that occur to you. The more you think about a topic, the more likely you are to come up with something that can earn you a little more credit for your answer. I never deduct points, so it can't hurt to add your own thoughts.